After Israel raced ahead to vaccinate much of its population and reopened its economy in March, the Mediterranean nation became a lode star for the world.

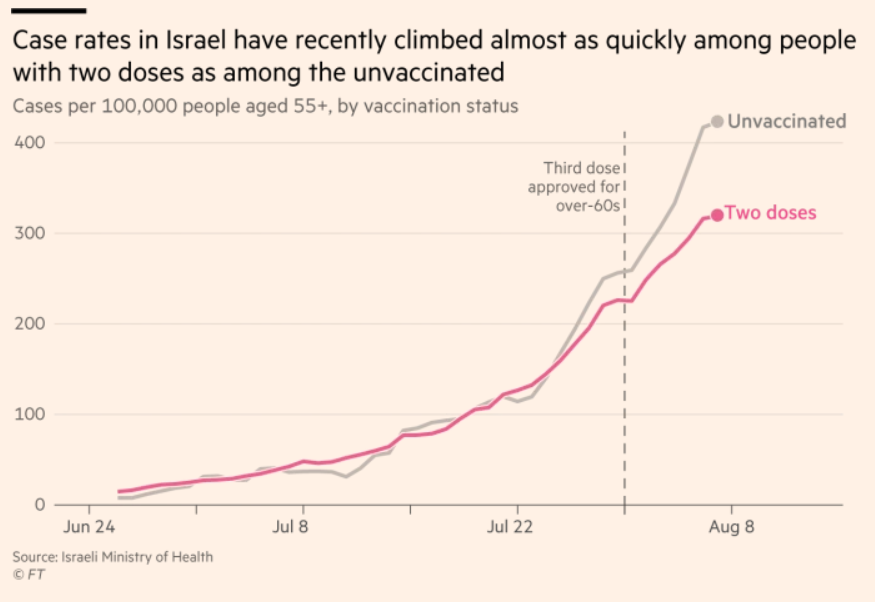

For five months Israelis enjoyed a taste of post-pandemic freedom, with jubilant, mask-free street parties and crowded restaurants. But now, with Israel’s coronavirus infections soaring to highs last seen in February and the public braced for another potential lockdown, scientists are asking what has gone wrong in a country in which 80 per cent of adults have been double jabbed.

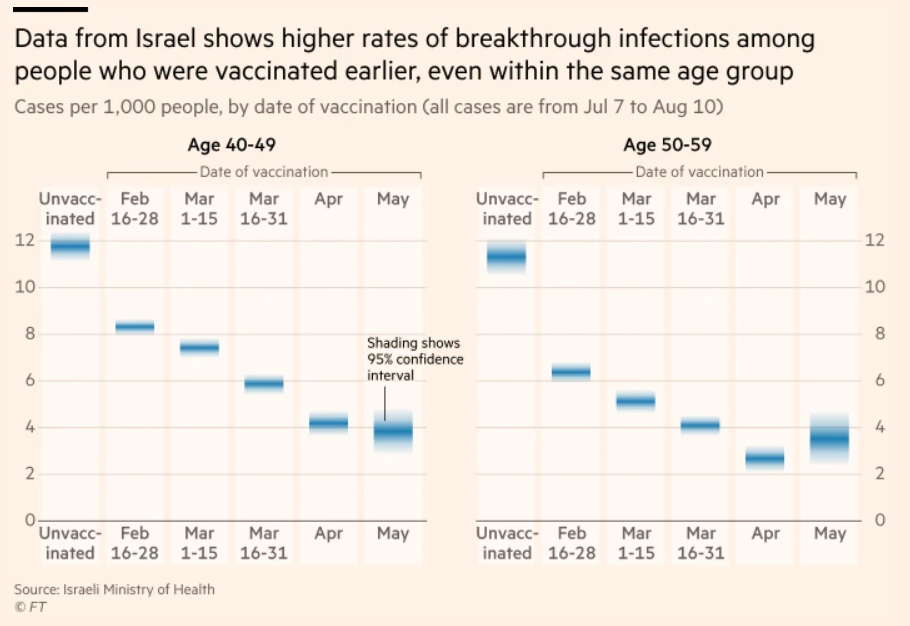

The answer, slowly taking shape in hotly contested data, is that the protection conferred by the BioNTech/Pfizer two-shot vaccine, which Israel has used almost exclusively, appears to fade over time faster than anticipated, increasing the risk of “breakthrough” infections. This eventually leaves those inoculated first — generally the oldest and most vulnerable — at increasing risk of infection and severe illness.

At the Sheba Medical Center, the largest in Israel, researchers identified the trend early. Monthly blood tests of medical staff, many of whom had been inoculated in December, started to show declining antibody levels and significant falls by June, said Arnon Afek, a top official at the hospital chain.

Antibody levels can sometimes decline without having an impact on efficacy but, at about the same time, Sheba hospitals began to note a rise in elderly, vaccinated people testing positive and seeking care.

“It was quite alarming,” said Afek. “After around six months, we realised that the level of antibodies in our staff was falling and, across Israel, there was an increase in the number of patients. And this was happening in parallel with the Delta [coronavirus] variant.”

By August, according to the health ministry, studies showed the Pfizer vaccine’s efficacy against infection falling to 39 per cent, and to as low as 16 per cent for people who had their second shots in January.

Most worryingly, the vaccine’s efficacy for the prevention of severe disease in the most vulnerable cohort — Israelis aged over 65, most of whom were double-jabbed by January — had dropped to 55 per cent, the ministry said.

Immunologists and experts, both in Israel and outside, have questioned the precision of that data, which the Israeli government released quietly and without any clarity on its methodology.

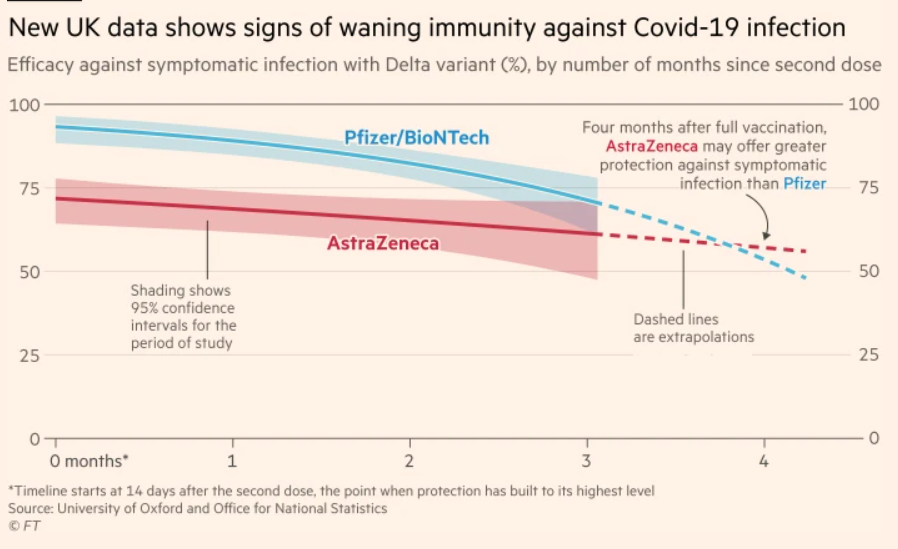

Other international studies have also shown lower efficacy for the Pfizer vaccine against the Delta variant and waning immunity over time, but the estimated declines have generally been smaller. An Oxford university study published on Thursday found that the efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine against symptomatic infection almost halved after four months.

Pfizer, which has worked closely with Israel during the pandemic and is pushing for the use of boosters globally, supported the government’s assessment. “These latest data from Israel are consistent with the epidemiological trends we have been observing and reinforce the need for a booster dose to re-establish maximum protective efficacy,” Pfizer said in response to questions.

Eran Segal, an adviser to the Israeli government and a computational biologist, said the efficacy of the vaccine was clearly falling over time. “If it weren’t for what seems to be a waning effect, we wouldn’t be seeing such high numbers,” he said.

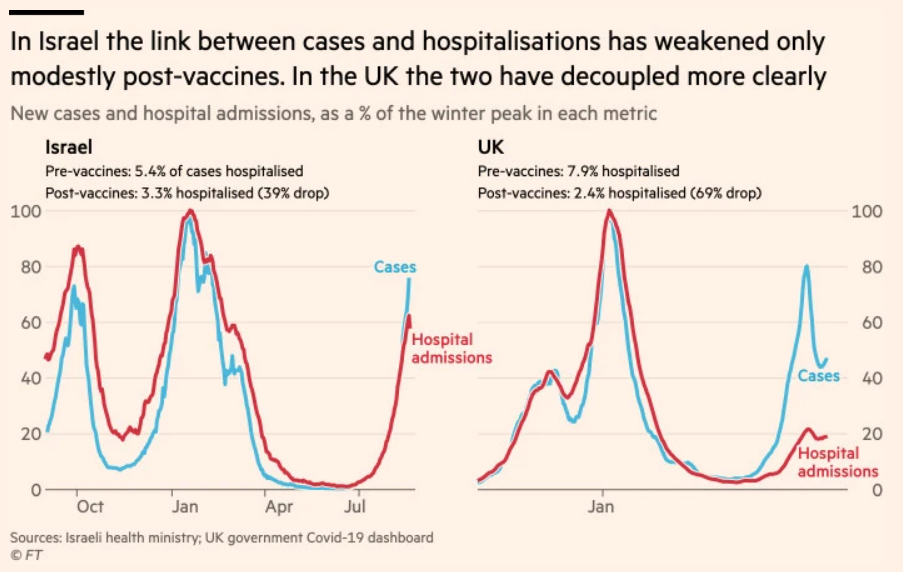

More concerning than the numbers testing positive was the number requiring hospitalisation. As Delta took over in the UK, the vaccination drive meant the proportion of coronavirus cases requiring hospitalisation fell by 70 per cent — the so-called decoupling between infection and the need for hospitalisation.

In Israel, where more of the elderly had been vaccinated earlier and Delta arrived later, that number only fell by 40 per cent, a trend that experts, including Segal, said showed the vaccine’s protection against severe illness had started to wane over time.

Israel has the capacity to handle about 1,200 Covid patients with severe illness, and by mid-August, half of those hospital beds were full.

Speaking at a cabinet meeting on Sunday, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett said: “Paradoxically, the most vulnerable group right now are those who’ve been inoculated with two doses and [have yet to receive] the third.

“The’re going around with the sense they’re protected — they don’t understand the second dose erodes over time against the Delta strain.”

In an effort to avoid another national lockdown, Bennett announced an almost $800m plan to double hospital capacity to deal with the severely ill. On July 30 Israel also became the first country to give a third shot of the Pfizer vaccine as a booster.

“The decision should have been taken earlier, but it was still a very, very courageous decision,” said Afek, who was previously the top civil servant at the health ministry. “At the time, the US Food and Drug Administration was saying a third shot was not necessary, so it took a lot of bravery to go ahead without the backing of the FDA.”

The FDA did not authorise third doses of the vaccine until August 13, and only for immunocompromised adults. Israel initially administered boosters to people over 60, then to those over 50 and, since Friday, to people over 40.

Some of the early data on the impact of the booster shots looks promising. At Maccabi Health Service, a large healthcare provider, the vaccine’s efficacy had shot up to 86 per cent just seven days after the injection, said Anat Ekka Zohar, who ran a study of about 150,000 triple-jabbed people over 60, of whom only 37 people caught coronavirus in the first week after the booster.

“The triple dose is the solution to curbing the current infection outbreak,” she said.

But Aaron Richterman, an infectious disease researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, cautioned that although the immune system tended to respond quickly to booster vaccinations, it was too early to measure their impact.

People who were “very early adopters” of boosters were likely to be different in terms of “occupation, risk aversion, healthcare-seeking behaviour” to those who chose not to seek a third shot, making comparisons difficult, he said.

“Even the most careful analyses can remain biased if the populations being compared are very different,” he added.

by Mehul Srivastava in Tel Aviv and John Burn-Murdoch in London AUGUST 23 2021